A crucial part of our Lenten journey is reconciliation. Reconciliation with each other, with God, and with ourselves. Forgiveness is easy enough in principle, but the experience is always painful and many of us stumble, sometimes wrestling for long periods with the notion of blotting out a wrongdoing that has stung us so badly.

But over the past week the Spirit has revealed to us, through the daily Mass readings, a deeper understanding of what it means to forgive.

Consider what the following readings all have in common…

On Thursday of the second week of Lent, we heard in Jeremiah 17:5-10 about the man who trusts in the Lord being “like a tree planted by water, that sends out its roots by the stream, and does not fear when heat comes, for its leaves remain green, and is not anxious in the year of drought, for it does not cease to bear fruit.”

The next day, we heard the story of Joseph in Genesis 37:17-28, and watched his brothers tear his cloak from him and throw him into a pit; but his life was spared and he was taken to Egypt where, as we know, he would go on to become very prosperous.

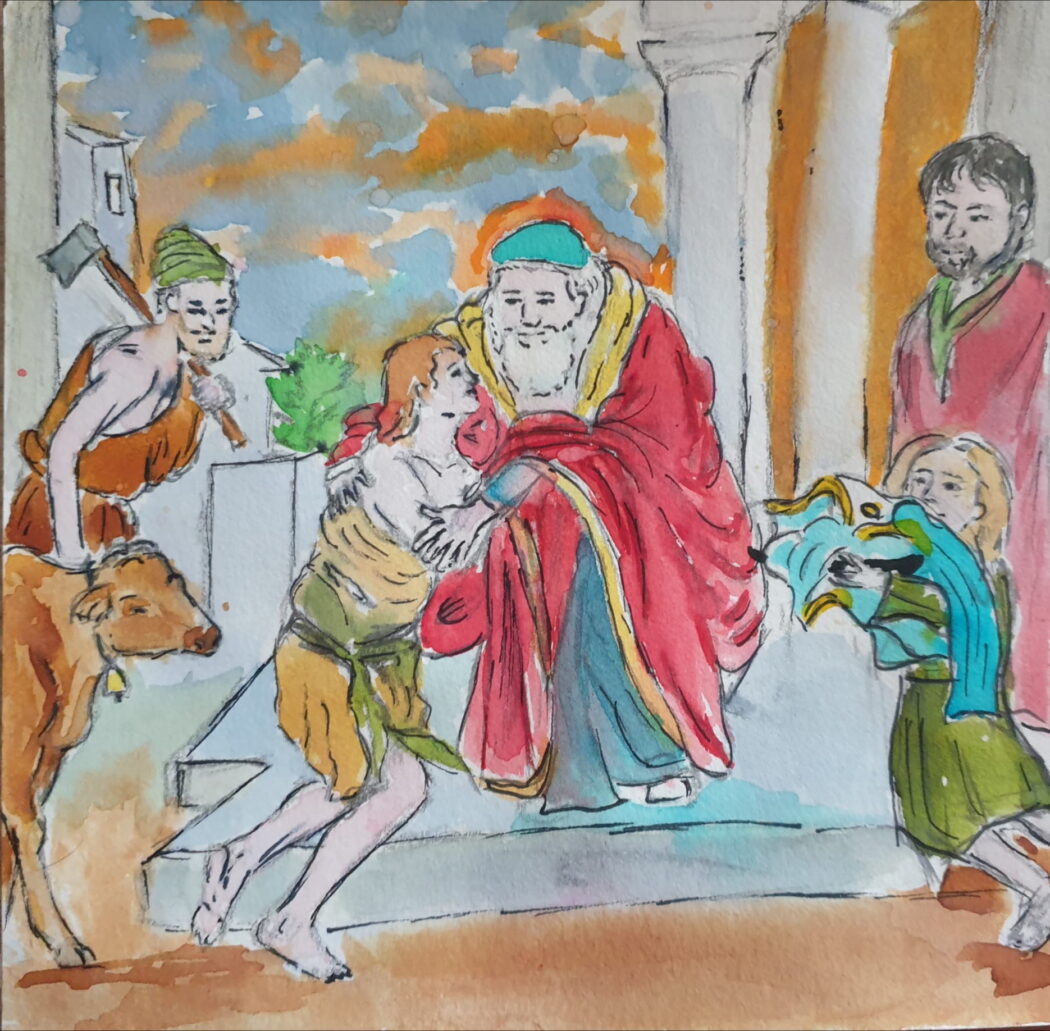

On the Saturday, in Micah 7:18-20, we hear that God “does not retain his anger for ever, because he delights in steadfast love.” Then in the Gospel we hear the famous story of the prodigal son, who left rich and found himself desitute, and we encounter the hardness of heart of his brother, who stayed and remained comfortable, upon his return.

What all these readings have in common is that they present an individual whose every crucial need has been satisfied in the Lord, leaving them free to not demand their fulfilment from other people.

The tree planted by water in Jeremiah has no need to desperately compete with the roots of other trees, or demand that they give way to it, because it knows what it needs and recognises the Lord as a caring steward who provides. It can peacefully remain dwelling in peace with those trees on either side, all reaching towards the same source of water which they know will provide for them all.

Joseph knew that he was loved by his father, and God spared his life from the murderous plans of his jealous brothers. Eventually, thanks to the freedom in which he later finds himself, Joseph was able to forgive his brothers their debt against him because he knew he did not rely on them for his freedom, dignity or purpose. He found those things in the Lord, and relied upon him for his needs.

The prodigal son’s brother, having stayed, has lived in his father’s total providence. When, out of jealousy, he despises his father’s generosity towards this son who betrayed them both, his father assures him that “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours.” There is nothing that the elder son lacks, and so there is no necessity for him to hold his prodigal brother in distain.

In Micah, we are told that God is free to blot out our debts because he is fully satisfied by his own love; and not just any love, it’s his “steadfast love,” that doesn’t waver or double-guess itself. God’s heart isn’t insecure or grasping, and so he can write off our debts whilst losing nothing. It is in this love that God has created the universe, and it is this love within which our lives unfold and ultimately make sense.

In all of these situations, God provides for his children’s needs and frees them from the need to demand fulfilment from one another. In some cases, an individual recognises this and is able to forgive, resting in the Father’s providence. Yet sometimes fear, lack of trust, and greed leave us feeling compelled to demand more of our neighbour, and thus begins the downward spirals of jealousy, bitterness and violence. The prodigal son’s elder brother is free to forgive, but chooses jealousy, and chooses to hold his brother to a debt that he never actually owed him.

In order to truly forgive, we must recognise what our needs are and identify the ways in which our Father in heaven fulfils them. We must trust that he desires to satisfy our needs, and trust his ways of doing so. This frees us to unchain other people from the debts we demand they pay us, whether that is through a desire for recompense, or a yearning for affirmation, or through an expectation that they serve or satisfy us in particular ways.

Let your Father take your hand and look after you.

If we demand our satisfaction from others, we will never be free to forgive them when they fall below our expectations (as they inevitably will, many times, and we them). But if we can recognise, like the man in Jeremiah, where to find the true source of water for which we thirst, then we can stand side-by-side with the other broken pilgrims alongside us and trust in the Father who provides tenderly for each of us. We can forgive, because the shortcomings of others are not what decide the providence of God.

Real forgiveness lies in resting in our sonhood and daughterhood, trusting that he knows how to satisfy our hearts, and therefore loosening our grip on those around us. We were never designed to be limpits clinging to one another; we are children of God, noble, upright and with an inherent dignity that no wrongdoing can take away, and the Father is calling each one of us home.