As society grapples with the ever-shifting sands of our culture today, a gradual trend has arisen. The term ‘Cultural Christianity’ has been emerging in current events and debates. Some prominent figures in public discourse have associated themselves with Christianity, yet intentionally hold back from a wholehearted approach to the faith. As people of faith, how can we understand the tension between the desire to merely associate with Christianity, and the desire to practice the faith with sincerity?

In 2024, a declaration made by Dawkins gave rise to significant debate around the topic of ‘cultural Christianity’. Dawkins was one of the prominent leaders who spearheaded the New Atheist Movement, which gained significant notability in the first decade of the 21st century. He declared himself to be a “Cultural Christian,” while simultaneously denying any of the fundamental claims of Christianity. This marked a clear moment of a shift in public thinking about faith and religion.

In the early 2000s the New Atheist Movement was in full swing, demoralizing anyone with a belief in the transcendent. Initially the attack on religion was indiscriminate and broad, sweeping over all forms of faith, but enthusiasm for the movement has dwindled over time, fading away from the news headlines.

With the steadily falling numbers of Christians in the Western world, the repercussions of abandoning the faith are becoming more apparent. Multiple public figures have shared concerns about the unfortunate consequences that the nation would face if Christianity truly disappeared from the western world. Many find solace in the presence of Christianity within a world that appears to lack any fundamental core beliefs. They see ‘cultural Christianity’ as a pathway towards a sense of meaning, but they feel no obligation to fully commit to all the spiritual and moral obligations that Christianity entails.

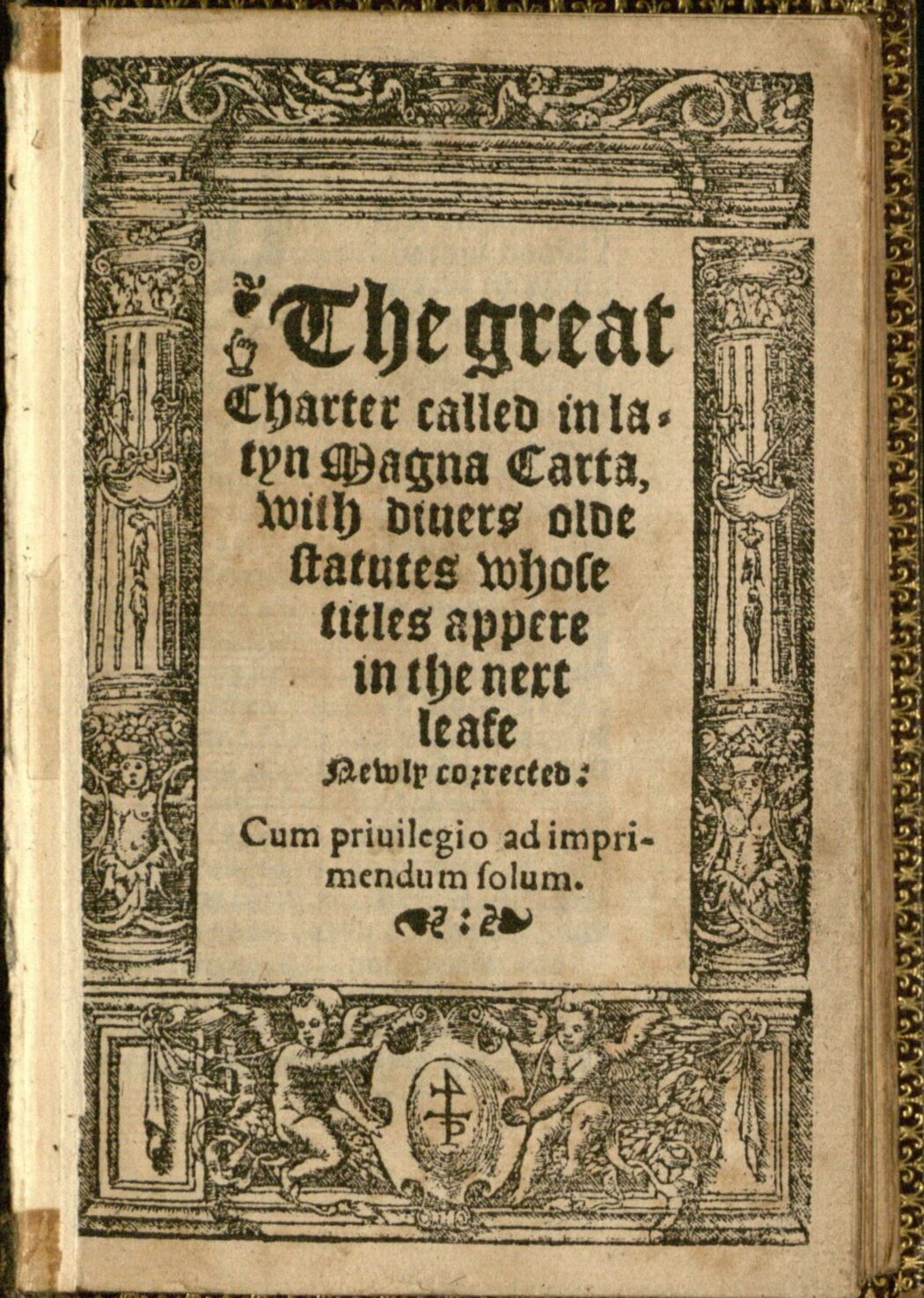

Sometimes it is only when one loses something that they realise how valuable it was in the first place. We unknowingly take certain things for granted until they disappear. The western world has nurtured Christianity for centuries, to such an extent that it is hard to imagine that Britain was once completely pagan before the advent of Christian missionaries proclaiming the good news of Christ. As Britain slowly accepted Christianity as the major religion, its culture and values also changed over time. Christian principles have been the driving force behind some the greatest positive social changes to have blessed the British Isles. The Magna Carta, the first legal document to claim that even the ruling king is to be subject under the law, is constructed from a Christian understanding that all people are subject to God’s laws. William Wilberforce clung fiercely to his Christian principles in the battle to end slavery in the British Empire. English Common Law has been heavily influenced by biblical principles.

The historian Tom Holland has spoken widely at the profound effect that Christianity has made on the western mindset. In his book ‘Dominion, The Making of the Western Mind,’ he claims that “People in the West, even those who may imagine that they have emancipated themselves from Christian belief, in fact, are shot through with Christian assumptions about almost everything…All of us in the West are a goldfish, and the water that we swim in is Christianity, by which I don’t necessarily mean the confessional form of the faith, but, rather, considered as an entire civilisation.” Some may be surprised at such statements, considering the many foibles of western society over the centuries. But we must not turn a blind eye towards the fingerprints of God on these societies, leaving upon them signs of a more Christ-like ethos. Our cities are peppered with visible symbols of this heritage, primarily in the form of churches, monuments and great charitable establishments. Dawkins himself confessed that it would indeed be a shame to lose the cathedrals scattered across Britain, and admitted to still cherishing other fragments of Christendom, right down to singing Christmas carols.

But it is precisely here that the keen eye will spot the answer to our conundrum. Too many reduce Christianity to a ‘gift-bearer’ status, enjoying the moral values society has inherited (compassion, generosity, justice, to name a few), hence turning religion into a consumer good. Dawkins’ beloved cathedrals became, for him, a treasure to possess, rather than a place to honour and worship his Creator. Many of the civil structures upon which our society depend are all apostolates constructed by those with a desire to builds God’s kingdom on earth. At the very least, to lose these would bring great discomfort and inconvenience to many. But Christ, during his time in public ministry, hastily departed from the communities who came to him seeking earthly commodities; his primary invitation was to relationship, even at the expense of earthly comfort. Christianity is fundamentally a relationship, and the cultural benefits are the good fruits borne from that.

Very few of us would admit to being content with receiving a gift with no care for the gift-giver, or of admiring a great artwork with no thought for the artist. Take one look at the state of proprietary laws nowadays, and the notion of not considering the creator becomes ludicrous. We should feel uncomfortable at the prospect of enjoying God’s gifts without seeking relationship with him, as Dawkins so comfortably professed doing. Rather, God lavishes these gifts upon us in the joy of his fatherly love and invites us to know his heart through them. The gift must always lead to the gift-giver.

Let us not cling to Christianity for utilitarian purposes.

Instead, let us remind ourselves of what God truly asks of those seeking to see his kingdom come. We are asked to be light, shining not for our own sake but rather so that others may know the way. We are asked to be salt, dying to ourselves in our service so that others may flourish. The Kingdom of heaven is compared to a grain of yeast; we are these grains and must have the courage to become almost nothing so that the kingdom may rise. To be a Christian may feel lonely at times, and our experience may be one of material and temporal insecurity. At these times, we must resist the temptation to wrap ourselves in worldly comforts. Our lives are a gift, as are the material comforts of Christianity in our culture and society, and everything must lead us back to God. The invitation is ultimately to relationship, rather than to a cultural joyride.

Dawkins was right to see the goodness in the earthly signs of the Kingdom of Heaven, but in establishing his ‘Cultural Christianity,’ he strapped a pair of blinkers to his eyes and settled for a life trajectory that would totally miss its purpose and fulfilment. We must cling to Christianity because it is our way to relationship with the one who created us, and the one to whom we are returning at the end of this life.

God never forces our hand. He never forces us to acknowledge him, but if we have the privilege of recognising his work, how could we then ignore him? Cultural Christianity is a signpost for those searching for truth and meaning. Could you live with only going half way?